Katie Babcock

Many breastfeeding mothers need to take over-the-counter or prescription drugs, but they’re often concerned about how these medications might affect their babies. Researchers from the University of Toronto are now creating guidelines to help women navigate this complex landscape, ensuring their children stay safe and healthy.

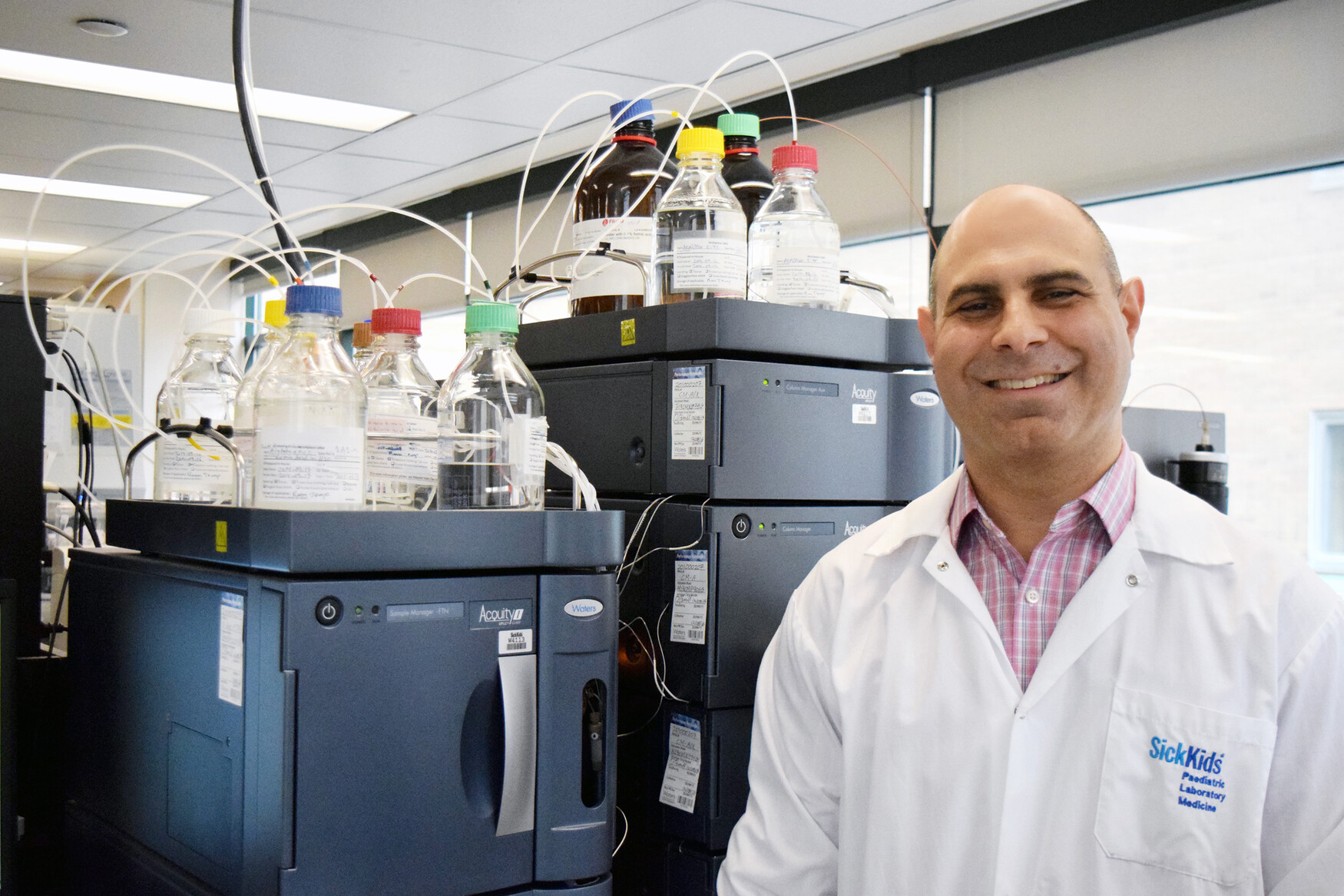

“Now more women are breastfeeding and for longer periods of time,” said David Colantonio, a professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and clinical biochemist at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). “It’s important to understand whether certain drugs can affect the baby through breast milk, and how we can avoid potentially dangerous situations.”

Approximately 60 to 70 per cent of breastfeeding women are using some form of medication. But how these drugs are transported through breast milk is poorly understood because pharmaceutical companies can’t conduct trials on nursing mothers.

Colantonio, who also oversees the diagnostic labs at SickKids, began creating guidelines after receiving numerous inquiries from concerned mothers.

Working with Shinya Ito, from U of T’s Faculty of Pharmacology and Toxicology and Head of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at SickKids, Colantonio is researching over-the-counter drugs, like sleep medication and antihistamines, and prescription drugs for conditions including Crohn’s, colitis, arthritis and depression.

The impact of this research and resulting guidelines could be huge.

“We had a baby who was admitted to SickKids for seizures,” said Colantonio. “We discovered that the mother had switched anti-depressants a few weeks prior to the baby’s symptoms. We took samples from the infant and mother, and we figured out that the infant’s exposure through breast milk was sufficient to cause seizures.”

Using specialized technology, called high pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, the researchers can accurately measure any drug at very low levels.

“We know some drugs won’t be expressed at all into breast milk, due to their transport mechanisms,” said Colantonio. “Other drugs will be there in copious amounts, and a lot of other drugs will fall somewhere in the middle.”

Colantonio and his team are interested in providing breastfeeding women with more options. “With some drugs, perhaps women can take their medication, ‘pump and dump’ and then safely feed several hours later.”

The team is also studying how to block the transport of some of these drugs with naturally occurring nutrients. For example, they’re researching whether folate could block methotrexate, a medication used for rheumatoid arthritis.

Once they gather enough data, they plan to develop guidelines within the next two years. In the meantime, they’re providing individual guidance to women who have questions about breastfeeding while taking medication.

“We don’t think that women should necessarily have to choose between taking their medications and breastfeeding,” said Colantonio. “We want to offer women better alternatives and to keep babies safe.”